Child psychiatric disorders, such as oppositional defiant disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), can feature outbursts of anger and physical aggression. A better understanding of what drives these symptoms could help inform treatment strategies. Yale researchers have now used a machine learning-based approach to uncover disruptions of brain connectivity in children displaying aggression.

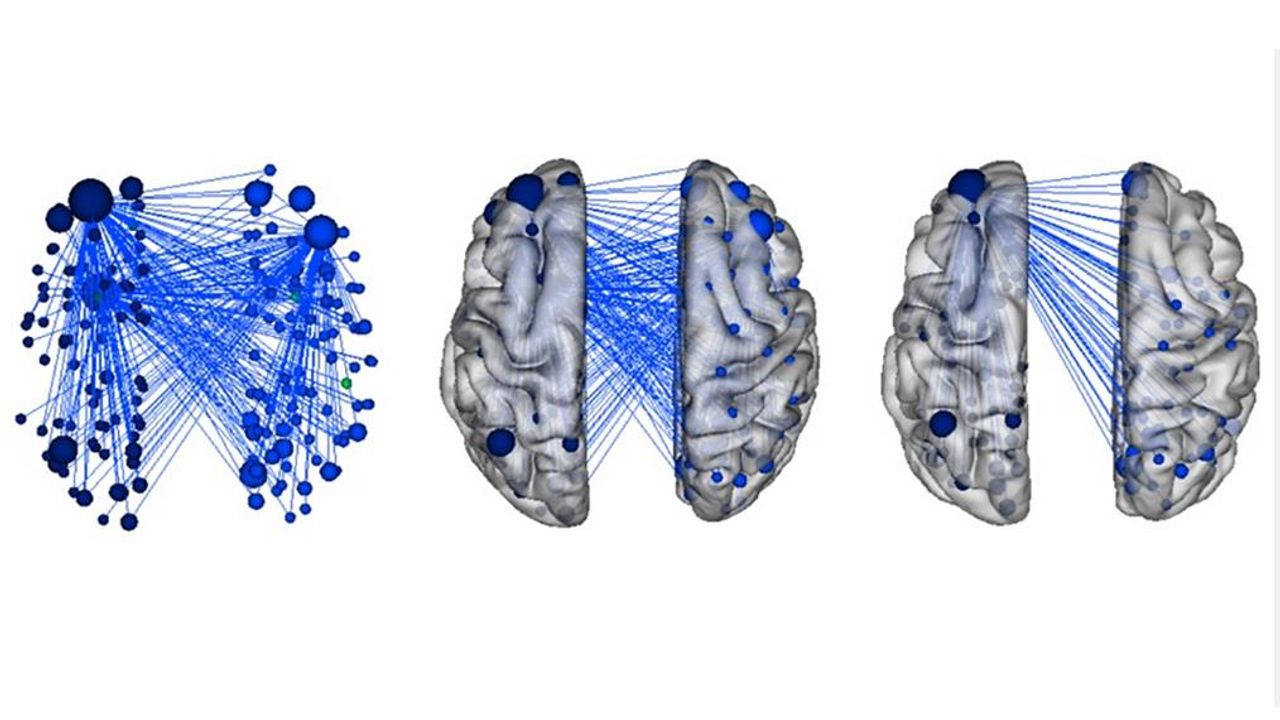

While previous research has focused on specific brain regions, the new study identifies patterns of neural connections across the entire brain that are linked to aggressive behavior in children. The findings, published in the journal Molecular Psychiatry, build on a novel model of brain functioning called the “connectome” that describes this pattern of brain-wide connections.

“Maladaptive aggression can result in harm to self or others. This challenging behavior is one of the main reasons for referrals to child mental health services,” said Denis Sukhodolsky, senior author and associate professor in the Yale Child Study Center. “Connectome-based modeling offers a new account of brain networks involved in aggressive behavior.”

Discover The World's MOST COMPREHENSIVE Mental Health Assessment Platform

Efficiently assess your patients for 80+ possible conditions with a single dynamic, intuitive mental health assessment. As low as $12 per patient per year.

For the study, which is the first of its kind, researchers collected fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) data while children performed an emotional face perception task in which they observed faces making calm or fearful expressions. Seeing faces that express emotion can engage brain states relevant to emotion generation and regulation, both of which have been linked to aggressive behavior, researchers said. The scientists then applied machine learning analyses to identify neural connections that distinguished children with and without histories of aggressive behavior.

They found that patterns in brain networks involved in social and emotional processes — such as feeling frustrated with homework or understanding why a friend is upset — predicted aggressive behavior. To confirm these findings, the researchers then tested them in a separate dataset and found that the same brain networks predicted aggression. In particular, abnormal connectivity to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex — a key region involved in the regulation of emotions and higher cognitive functions like attention and decision-making — emerged as a consistent predictor of aggression when tested in subgroups of children with aggressive behavior and disorders such as anxiety, ADHD, and autism.

These neural connections to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex could represent a marker of aggression that is common across several childhood psychiatric disorders.

“This study suggests that the robustness of these large-scale brain networks and their connectivity with the prefrontal cortex may represent a neural marker of aggression that can be leveraged in clinical studies,” said Karim Ibrahim, associate research scientist at the Yale Child Study Center and first author of the paper. “The human functional connectome describes the vast interconnectedness of the brain. Understanding the connectome is on the frontier of neuroscience because it can provide us with valuable information for developing brain biomarkers of psychiatric disorders.”

Added Sukhodolsky: “This connectome model of aggression could also help us develop clinical interventions that can improve the coordination among these brain networks and hubs like the prefrontal cortex. Such interventions could include teaching the emotion regulation skills necessary for modulating negative emotions such as frustration and anger.”